Perhaps the greatest threat to the workforce in the 21st Century is a newly designated phenomenon called occupational burnout. The phenomenon is not new, and it has been studied from a variety of disciplinary angles before. My mother used to ominously call its more serious stages, “a nervous breakdown.” What is new is that the World Health Organization has had to recognize that it is happening, without knowing quite how to create a framework yet for a medical or behavioral health diagnosis.

I first noticed the phenomenon in 1991 before I knew what it was or what to call it. I was a plebe at the United States Military Academy at West Point, and I had collided with Princeton’s goalkeeper while playing soccer for Army, resulting in eye surgery at Walter Reed. When I returned to school after a month, I had to make up a month of work while keeping up with new work, all with a patch over one eye. I would wake up at 0520 every day, go to breakfast, class, lunch, then class again, only to study from 1500 hours (3pm) to midnight every day.

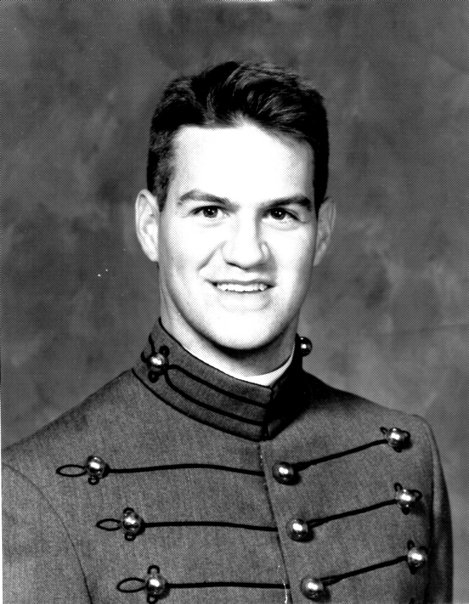

Cadet Chris Cairns after recovering from eye surgery

I had to go to the ER a couple of times because I did not know what was happening to me physically. It turned out that I had muscle tension headaches from studying all day–every day–with only one eye. I would not have made it as far as I did were it not for my Tactical Officer, then CPT Jeffrey Snow, future Major General and Commander of US Army Recruiting Command, as well as a whole team of great Protestant Chaplains.

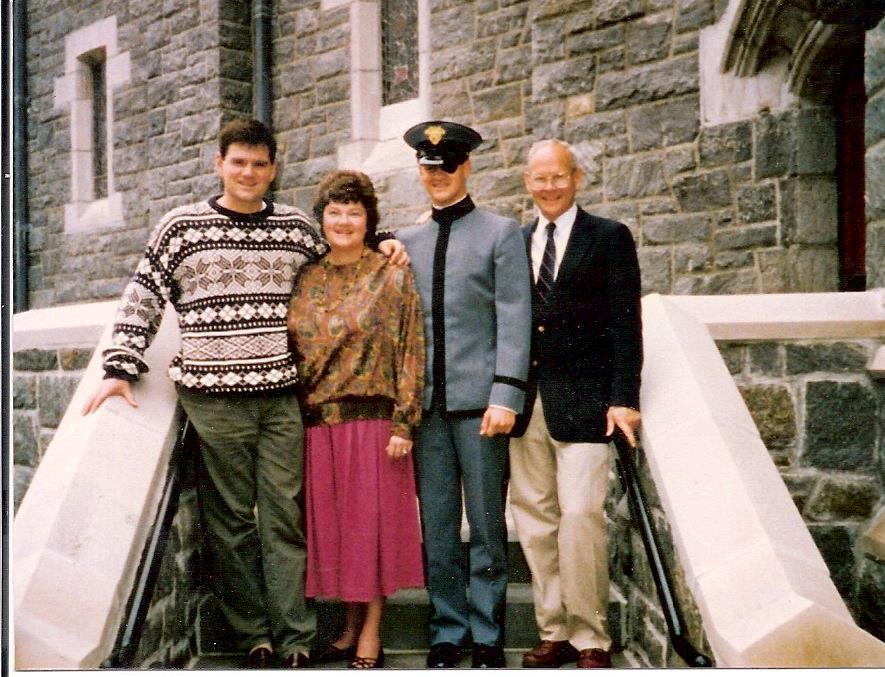

By December of that first year, I was physically, emotionally, mentally, and spiritually exhausted, with yet a semester to go. I remember calling my father, LTC (Ret.) Robert B. Cairns, Vietnam Veteran, West Point class of 1961–whose uncle and father were classes of 1932 and 1933–and telling him I didn’t think I was going to make it. He wisely counseled me to finish the academic year, saying he’d support me wherever I decided to go next. I was not fun to be around that semester, as one of my good friends and classmates, Steve Sprengnether pointed out. I had become toxically negative. I made some bad decisions between January and graduation, and I’m fortunate I was not caught out after TAPS by the MPs. Those are stories better told over a preferred beverage. When I transferred to the University of the South the following year, it took me another whole year to recover.

Cadet Chris Cairns, with eye patch, and brother, Gulf War Apache pilot CPT Craig Cairns, mother Terry, and father LTC Robert Cairns, Deputy Director of Physical Education at West Point and Director of Physical Education at Virginia Military Institute.

That was to be my first experience with burnout, but not the last. Before coming into the Army as a Chaplain, I had been in full-time ministry for almost 20 years, all the while flirting with deep stages of burnout yet never quite achieving it. I finally got there in year 6 of planting a new church in the wake of a denominational schism while serving as a regional leader of a church planting network. When the church I was leading refused to give me the sabbatical I so desperately needed, I resigned with absolutely zero energy left in my body, soul, or spirit. As my soccer coach at Sewanee, Coach Matt Kern, put it: I had “left everything I had on the field.”

“When it comes to the sustainable maintenance of our primary weapon systems, we are taking better care of our tanks, Bradleys, and helicopters than we are our primary weapon system: the American Soldier.”

I recovered for the following two years, teleworking for Alpha USA and preparing to become an Army Chaplain. While getting back into shape from sedentary pastor life to Army Chaplaincy, I ruptured an Achilles’ tendon playing soccer just before turning 40 and entering Chaplain Basic, “hamstringing” my efforts ever since to be in elite shape, with surgery following surgery for the last seven years. In my first unit, I jumped–with one good and one bad foot–into the operational tempo of a globally ready elite combat unit, the 1st Squadron, 4th Cavalry, also known as Quarterhorse.

As I looked around at the operational tempo of our units in a Garrison training environment, I was astonished to learn that many of our serious incident reports could be directly linked to occupational burnout causes and symptoms. I began to research the concept, but I found very little in the way of organized, scientific research describing the stages of burnout and its impact on the Active Army. When I first broached the subject with my Commander, then LTC Fred Dente, his legitimate pushback came as another wake up call to the problem: “I give my Troopers one four-day weekend a month in addition to 30 days of leave a year. I only have a certain number of training days left per month to accomplish the tasks we’re given.” That helped me begin to look at the problem set from the Commander’s perspective. It became clear that it was not just an organizational problem, but also a problem of Soldiers not doing the right things in the margins of their time left over by the Army, things that would refresh their souls and refresh and recharge their batteries.

At the 1-4 CAV, we built a standards excheck–or execution checklist–that assisted us in identifying moderate to high risk Soldiers. In addition, I built a counseling communications tool that seemed to depressurize our higher risk Soldiers. I did not know how spoiled I was at that time before ARSTRUC dismantled us, to be surrounded by such effective leaders, including COL Dente, CSM Wendell Franklin, LTC George Bolton, and LTC Brad Nelson. But I took those lessons with me to the next unit, in the process of standing up 3-66AR from scratch with CSM Dwayne Uhlig and then LTC Jorge Cordeiro. In only nine months of gathering people and building systems, 3-66AR defeated Blackhorse at the National Training Center at Fort Irwin, a testament to a great leadership development ecosystem of which I was only a bit part.

“Job burnout is a special type of work-related stress — a state of physical or emotional exhaustion that also involves a sense of reduced accomplishment and loss of personal identity.”

Over the course of my time at the 1st Infantry Division, I continued to develop the concept of occupational burnout mitigation training for Soldiers and Spouses that I later used for the 3000 Warrant Officers and Candidates that come through the Warrant Officer Career College every year. I continue to apply those lessons in my current role as a Chaplain to Recruiters, one of our more at risk populations for a host of extra pressures.

Chaplain Cairns addressing Warrant Officer Candidates at the Warrant Officer Career College, Fort Rucker, Alabama

So what do we do about a phenomenon that is defined differently by various academic disciplines and schools of thought? Perhaps we ought to first take a look at where the Army has already been addressing these issues, and where the civilian sector may also have something to teach. In the Army, we do not allow aviators to continue to fly for indefinite periods beyond the established and studied limitations of one single human being. Likewise we do not allow surgeons to perform their duties indefinitely beyond the limitations of one single human being. When it comes to the sustainable maintenance of our primary weapon systems, we are taking better care of our tanks, Bradleys, and helicopters than we are our primary weapon system: the American Soldier. Army medicine sees the symptoms and prescribes anti-inflammatories and 6 weeks of physical therapy. Army Chaplains see the symptoms, and we recommend greater spiritual health and connectivity to faith communities. Behavioral health sees the symptoms and might over-diagnose PTSD.

These are all pieces of the puzzle, but put together, we might all be experiencing different parts of the same elephant in the room: occupational burnout. This is caused by the following three things: soul-crushing organizational operational tempos; individual, achievement-oriented, performance-based identities; and our entertainment oriented culture where we transition from the blue light screens of workstations and work phones to the blue light screens of home TVs, tablets, and personal smart phones, with little understanding of the difference between amusement and recreation. This combination is burning out our best and our brightest. (The lazy do not burn out. They find the path of least resistance around work). At stages 3, 4, and 5 of burnout, our will to continue to aim at excellence wanes, and we start losing relationships, marriages, and even lives.

The Mayo Clinic has defined job burnout in an article with some excellent lists of symptoms, causes, and lists: “Job Burnout: How to Spot it and Take Action” Mitigation is given short shrift in their article, but that is what I am intending to primarily address a bit further along. Here is how they define it: “Job burnout is a special type of work-related stress — a state of physical or emotional exhaustion that also involves a sense of reduced accomplishment and loss of personal identity.” Here follows the symptoms, causes, risk factors, and potential consequences. I have yet to be in a room full of Soldiers where they do not begin laughing out loud when looking at these lists, as they know that based on these lists, a) they have been burned out at some point in their career, and b) Army organizational leadership culture has a default setting that causes this phenomenon to occur quite naturally, often with devastating results.

Job burnout symptoms

Ask yourself:

Have you become cynical or critical at work?

Do you drag yourself to work and have trouble getting started?

Have you become irritable or impatient with co-workers, customers or clients?

Do you lack the energy to be consistently productive?

Do you find it hard to concentrate?

Do you lack satisfaction from your achievements?

Do you feel disillusioned about your job?

Are you using food, drugs or alcohol to feel better or to simply not feel?

Have your sleep habits changed?

Are you troubled by unexplained headaches, stomach or bowel problems, or other physical complaints?

If you answered yes to any of these questions, you might be experiencing job burnout. Consider talking to a doctor or a mental health provider because these symptoms can also be related to health conditions, such as depression.

POSSIBLE CAUSES OF JOB BURNOUT

Job burnout can result from various factors, including:

Lack of control. An inability to influence decisions that affect your job — such as your schedule, assignments or workload — could lead to job burnout. So could a lack of the resources you need to do your work.

Unclear job expectations. If you’re unclear about the degree of authority you have or what your supervisor or others expect from you, you’re not likely to feel comfortable at work.

Dysfunctional workplace dynamics. Perhaps you work with an office bully, or you feel undermined by colleagues or your boss micromanages your work. This can contribute to job stress.

Extremes of activity. When a job is monotonous or chaotic, you need constant energy to remain focused — which can lead to fatigue and job burnout.

Lack of social support. If you feel isolated at work and in your personal life, you might feel more stressed.

Work-life imbalance. If your work takes up so much of your time and effort that you don’t have the energy to spend time with your family and friends, you might burn out quickly.

JOB BURNOUT RISK FACTORS:

You might be more likely to experience job burnout if:

You identify so strongly with work that you lack balance between your work life and your personal life

You have a high workload, including overtime work

You try to be everything to everyone

You work in a helping profession, such as health care

You feel you have little or no control over your work

Your job is monotonous

Consequences of job burnout

Ignored or unaddressed job burnout can have significant consequences, including:

Excessive stress

Fatigue

Insomnia

Sadness, anger or irritability

Alcohol or substance misuse

Heart disease

High blood pressure

Type 2 diabetes

Vulnerability to illnesses

These are not symptoms that are unique to the Army, as the wider American culture is beginning to exhibit some widespread symptoms of a lack of self-care, and this is perhaps due to a variety of factors, as I mentioned, such as an overexposure to blue light from computers, smart phones, tablets, and video games in ways that lead to mental fatigue and brain exhaustion. The cultural product that Army Recruiters are receiving from American families and high schools are not young people who have been exposed to the rhythms of work and life that mitigate against burnout, often lacking connections to faith and Creator, connection to conscience, connection to community, and connection to Creation.

In the margins left over by the Army after we take the largest chunks of a Soldier’s time and emotional and intellectual resources, they often are not using their margins to refresh their souls so they can come back the following day or week with renewed vigor to attack the mission and aim at excellence. In addition, the organizational leadership culture of the Army tends to reward competence, capability, and capacity by scraping the tasks from the plates of the less competent onto their plate, filling their capacity to full and overflowing, diminishing the ability of our best and brightest to design a work/life balance that has sufficient room in the margins for investing in spouses and families.

In this diminished capacity for investing in renewal, refreshment and relationships in the margins left over by the Army, we are more tired, more impatient, have shorter fuses, and are more in need of rest than anything else. We then reach for the wrong things to take the edge off: drinking one too many; coloring outside the lines of covenant relationships; seeking amusement and entertainment rather than recreation and refreshment. There is nothing inherently wrong with amusement, but we need to distinguish between it and recreation. A-muse means “not think.” It is mentally checking out. It is playing video games and binging shows on Netflix, the sort of Quarantine behavior many of us reverted to during societal shutdown. Most often, however, these are not the sorts of activities that refresh our soul, and overcoming the inertia of exhaustion to get out and recreate is too much for us, and it takes us down.

I tell my Soldiers all the time that we volunteered for this Mission, and it is a great one: fighting and winning our Nation’s wars. We are one of the greatest forces for providing peace and security for global trade routes in human history, serving as the Western enforcement of our rules-based global economy. I believe very strongly in that mission, as a part of 105 years of unbroken Active Duty service in my family. However, an impersonal bureaucracy will allow us to sacrifice ourselves on the altar of that mission, just as Generals Grant and Sherman were willing to do during the Civil War. If we are expending our people in a commodification culture in which Commanders allow their Soldiers to do more, be better, and go faster to the breaking point, and we are breaking Soldiers in body, soul, and spirit, with much of our talent leaving the Army jaded and cynical, rather than continuing to be our best recruiting force, perhaps there is more that we can do at both the macro level as well as the micro, with the micro being me in the Chaplain’s office doing crisis counseling. We could just let this problem continue to fester.

Far better would be to train people how and why to protect themselves from occupational burnout, as well as how and why to train the force to protect themselves in preventative self-care. In addition, we must teach everyone how to notice the signs and symptoms in everyone within our spheres of influence to mitigate against worsening conditions, and if need be, do crisis interventions that account for the need of Soldiers to recover from the deep stages of occupational burnout when exceedingly poor decisions are made, sometimes even choosing permanent solutions to temporary problems.

Coming: “Designing the Life You Would Prefer: Part II, Burnout Mitigation and Recovery”